The Quarrymen

By Jim Tavener

The quarries in and around Morganstown are geological marvels that have been quarried since prehistory. Jim Taverner recalls working there with his father during the 1940s and 50s, and remembers some of the colourful characters and dangerous jobs

My father, Chris Taverner and his friend Bill Brown worked for F. Bowles & Sons (later to become British Dredging) as Company Secretary and Accountant respectively, before and during the Second World War.

In 1946, they decided to become self-employed and to that end, they formed Abbey Quarries Ltd. and also Abbey Sand & Gravel Ltd. They negotiated the leases of Tynant and Portabello quarries from Mr. Edwards of Taff’s Well. Portabello Quarry, on the eastern side of the valley was unsafe for further quarrying but the machinery at Tynant still had some years work left in them. The deal also included workshops at Moy Road in Taff’s Well.

The pair leased two sand dredgers, the Sand Moor (a converted ex-American Army triple screw Tank Landing Craft) and the Sandskipper, to suction dredge for sand in the Bristol Channel. They did this mainly beyond Steep Holm, thereby providing a complete aggregate solution for the post-war building boom. They operated the vessels from East Dock, Cardiff.

The machinery at Tynant itself included main and secondary stone crushers, grading drums for sizing the crushed stone, a Ruston Bucyrus 10RB excavator and three Bedford Tippers (two brand new and one Army surplus).

There was also an office, a weigh bridge and a safety shelter (with a reinforced concrete roof) which also served as a tea room for the quarry men.

On the B4262 Tynant Road were several large hoppers containing different sizes of aggregate and the tippers were loaded from these. Also in place, but not used was a gantry across the road for loading aggregate directly into rail trucks during the war years. These hoppers were sited where the present-day reconstructed lime kilns are situated.

I can remember two of the quarry men. One was the Licensed Shot Firer, Albert Sullivan who lived at Greenmeadow in Tongwynlais and the other was Ken Mortimer, lorry driver of Morganstown. As a small boy, I used to marvel at Albert Sullivan scaling the sides of the quarry, loaded down with a compressed air hose and heavy rock drills, and nonchalantly (or so it appeared) drilling the rock face and stuffing sticks of Gelignite down the holes.

When it was time for blasting, everyone sheltered in the tea room but I couldn’t resist watching the results of Albert’s labours from the doorway. On several occasions, there were hits on the Tynant pub roof.

My father would always take a hand at the hard work when there were staff shortages. On one Sunday, he was manning one of the big stone crushers. This entailed standing over the crusher jaws and using a large crow bar to dislodge blockages. Even at my adventurous young age, I considered this to be a fairly hazardous thing to do. I was manning the On/Off switch and following a cry of alarm from Dad, I threw the switch. Bouncing about among the rocks was a stick of Gelignite complete with fuse wire close by but no detonator cap! Phew!

On another occasion, Albert the Shot Firer, was going on holiday. Before leaving, he had blasted a large quantity of stone to last until he returned. Much of this material was still in very large boulders, far too large for excavator and crushers. These had to be broken up into smaller pieces and a process known as plastering was used. Some of the more elderly among you may remember the peace and quiet of a Sunday afternoon being disturbed by a series of explosions in fairly close order. This was plastering. It entailed taking a stick of gelignite, inserting a detonator cap and cutting a length of fuse wire to the required length. This was then ‘plastered’ to the boulder with mud to direct the power of the blast into the rock.

We had to set about a dozen of these charges all with different lengths of fuse, allowing us to light them all and make for cover behind the trusty 10RB excavator. You couldn’t be cavalier about the number of charges – they had to be counted at each detonation and if there was a discrepancy, a search had to be made to recover the missing delinquent.

All went well and I had lit my half dozen with the lighting stick and was running for cover but the old man dropped his stick among the boulders and resorted to matches and only just made it! My mother would have killed him if she had found out what we had been up to. If there had been a Health & Safety Executive, they would have had a field day. Those were the days!

There was also a character called Paul Tripp who had a blacksmith’s shop on the other side of the valley. There didn’t seem to be anything that Paul couldn’t make from a piece of steel, shoeing horses one minute and repairing excavator parts the next. I remember him being a giant but jovial man who seemed to be liked by everyone.

Lunches were invariably taken in the Lewis Arms in Ton with Ernie Hall the Butcher, Mr. Bennett the Garage, Maberly Parker (who had a Civil Engineering yard at Ynys Bridge) and many others.

After about fifteen years of operating, the machinery was just about worn out and with a building slump in the offing, it was decided to cease quarrying at Tynant and it closed for good in about 1958.

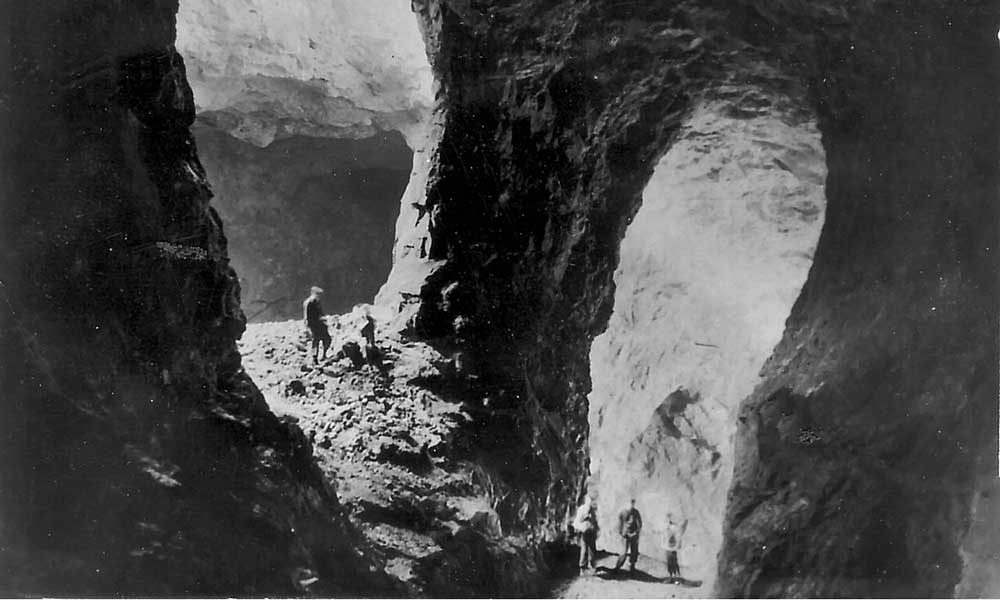

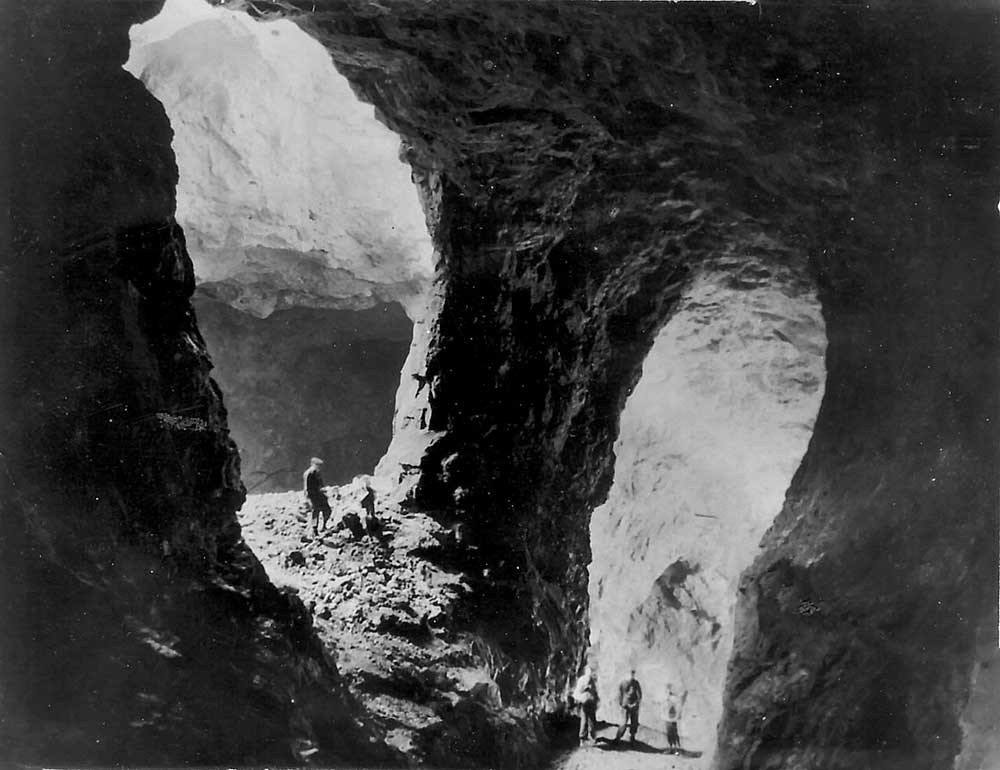

Many years later, my son Shaun introduced me to caving with the 2nd Rhiwbina Scouts. Over a few years, I discovered many of the caves in southern Wales and to my surprise, thoroughly enjoyed it. In order to gain access to various caves, many of them locked, we became affiliated to the area’s governing body using the name Rhiwbina Speleology Society – a pretty grand name for a small group of enthusiasts. On one of my last caving trips before old age, infirmity and pressure from my spouse put an end to adventure, I found myself roping down and swinging into the tiny entrance to a fascinating cave, Ogof Pen y Graig (I have since been made aware that the name is probably incorrect and that the Little Garth Cave is now connected to it), the entrance to which was on the vertical face of Tynant quarry.

After a long, tight bedding plane crawl, we entered a small but beautiful chamber with great formations. How they had survived the constant blasting operations at Tynant and at the Dolomite next door, I shall never know.

Talking of the Dolomite quarry, (later known as Steetley Quarry), for those of you who know the Little Garth, you will be aware that there were many areas of old mine workings and that attendant waste from these workings was put into convenient mounds.

My father arranged to remove many hundreds of tons of this waste which was mainly limestone, sent it through the crusher and hey presto, aggregate ready for the market!

I always thought that the old workings was a very spooky place. I think someone had fallen to their death in one of shafts in the 60s. I remember most of these shafts as being completely unguarded. I’m pretty sure too that the area was controlled by the War Department during WW2 and used to store important Government documents.

Be aware that the old Tynant Quarry and that the entrance to Little Garth Cave (the entrance is gated) is private property.

Jim Tavener, 2018