St Nazaire: The greatest raid of them all

Llandaff’s Bill Pritchard was one of 622 men who took part in an extraordinary raid on a German-held port during WW2. This is the true story of how a group of men turned the war.

28th March 1942 00:30 hrs

Under the cover of darkness, the British destroyer HMS Campbeltown and a convoy of 18 small craft slowly and quietly swept up the Loire estuary, deep in enemy territory.

Its target was the heavily defended Normandie dry dock at St. Nazaire in German-occupied France. In spring 1942, German U-boats were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic and the English Channel, while out in the North Sea, the giant German battleship Tirpitz, was waiting to be unleashed on Atlantic shipping convoys. St. Nazaire was the only German-held port large enough to service her on the Atlantic coast.

And so it fell to a group of brave men aboard HMS Campbeltown and the small ships, to put the dry dock out of service for good. Commanding the Campbeltown was Welshman Captain Beattie. And in one of the smaller boats, sat a man from Llandaff. His name was Bill Pritchard. The convoy was less than two miles away from its target when its cover was finally blown. The following events went down in history as the Greatest Raid of Them All.

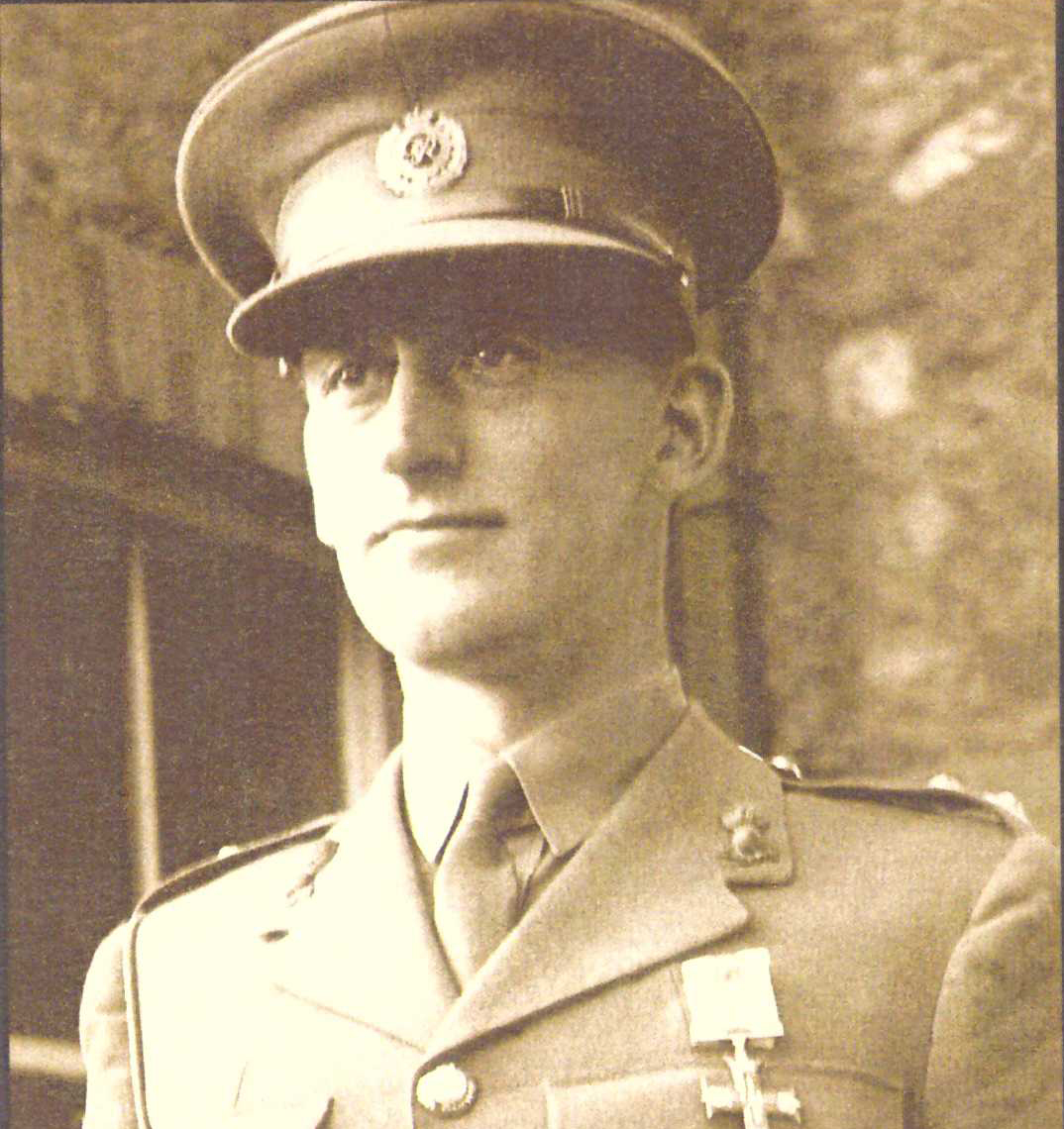

William Henry Pritchard was born on the 22nd October 1914. His father, Captain William Edward Pritchard MBE was Dock Master at Cardiff Docks and the family lived at Mill House, Mill Lane in Llandaff Fields.

After completing his schooling, Bill served an apprenticeship with the engineering branch of the Great Western Railway and was based at Cardiff Docks. Soon after, he joined the Territorial Army and was commissioned to the Royal Engineers: 246 (Cardiff) Field Company RE.

It was in early May 1940 that Lt. Pritchard was sent to Belgium where he led two reconnaissance parties, preparing for an Allied advance. Not long after arriving there, Bill was put in charge of blowing up a bridge, but before he could blow it up his group came under intense fire from German forces. Bill managed to achieve his aim of blowing the bridge up but within a few days, the situation in Belgium had become hopeless.

On 26th May, Bill and his group learned that they were to be evacuated back to the UK. They had to get back to the French coast with immediate effect where they would be collected. With the Germans hot on their tails, 246 carried out vital acts of demolition and built relief bridges to help relieve traffic congestion from retreating forces.

The Company’s transport was sent to the coastal town of La Panne where the Group drove their trucks into the sea one after the other. This created a jetty that the retreating men could walk along to the waiting ships.

Bill’s escape from the Dunkirk beaches was extraordinary in itself. By sheer chance, Bill was picked up by a boat that had been provided by his next door neighbour, Jack Neale. Upon arriving back in England, Bill was sent to Colston’s School in Bristol to reorganise. There, he was pleased to bump into his younger brother, who happened to be a pupil there.

After Dunkirk, Bill was promoted to Captain. He expressed regret that the French docks had not been destroyed before the evacuation. As such, the Germans had access to several key ports which gave their navy free reign to their warships in the Atlantic.

While on leave back in Cardiff, Bill made a study of German air attacks on Cardiff Docks, and came to the conclusion that placing explosives on vital equipment would be much more effective than blanket bombing.

In January 1942, Bill was ordered to report to Combined Operations Headquarters where he was instructed to plan an attack on St Nazaire and to train the commandos who would take part in it. It would be called Operation Chariot. Its aim would be to ram a destroyer packed with four tonnes of explosives into the gates of the dry docks at German-held St. Nazaire, destroy the facilities, and get back home again. It seemed an impossible task.

Training took place in Rosyth, Southampton, Cardiff and Barry. On one occasion, security at Cardiff Dock had not been alerted to the training and as the men with blackened faces started swarming the girders, the local policeman ordered their arrest.

After a meal at the Angel Hotel, the commandos assigned to the demolition work left for Falmouth. While waiting for their train at Cardiff General, Bill overheard one of the commandos guessing out loud that he thought they were headed for St. Nazaire. Afraid of a breach in security, Bill had the commando arrested on the spot.

HMS Campbeltown set sail at 2pm on 26th March 1942. It was accompanied by 18 small craft, and in its forward compartment was concealed four and half tons of high explosive encased in concrete. If the mission was to be a success, the ship had to hit the dock gates perfectly at just the right speed and at just the right angle.

Capt. Beattie, commanding the Campbeltown, had so far managed to guide the convoy into France undetected and was just eight minutes away from his target. Suddenly, the entire convoy was illuminated by the combined searchlights from both sides of the estuary. The Germans demanded identification and still aiming to deceive them, the British replied with a coded response stolen from a German trawler that they had apprehended in an earlier raid. It bought them very little time before every German gun opened fire. With a mile still to go, the German flag that had been raised aboard HMS Campbeltown was lowered and the British battle ensign was raised.

The ship was taking huge punishment but Capt. Beattie ordered the speed to be increased. Caught in the gunfire, the helmsman was killed outright and replaced by another, only for the replacement to be shot and killed too. Up stepped another replacement – it was Nigel Tibbits, the commando who had designed the bomb aboard the ship. Blinded by the searchlights, Beattie gave orders to Tibbits who steered the Campbeltown. The ship narrowly avoided a collision with a harbour wall, cutting through anti-torpedo netting strung across the entrance to the dock gate before Tibbits drove the ship up 33 feet (10 m) onto the gates.

With gunfire streaming into the bridge, Capt. Beattie looked at his watch and looked up. With a wry smile, he said: “Well there we are. Just four minutes late.”

The commandos then hurried to disembark and tackle their individual tasks. The key targets – the pumping station, lock gates, bridges, and other key buildings were destroyed.

Bill’s tasks were to control the timing of the demolitions and to attack targets of opportunity. These included two tugs that were berthed side-by-side. Bill and his corporal lowered charges between the two, sinking both of them.

But as dawn broke, it became apparent that the small ships that were to provide passage back to the UK had been destroyed. The raid was well and truly over and 168 commandos were dead. The sight of the Campbeltown riding high over the dock gates, still intact, drew crowds and souvenir hunters. The bomb had not gone off.

With no means of getting home, over 200 commandos were taken prisoner by the stunned German forces.

By 10am, Capt. Beattie was being held in a nearby hut. His German interrogator had tried belittling him and remarked:

“It’s no good ramming a stout caisson like that with such a flimsy ship.”

At that moment, there was a huge explosion. The bomb inside the Campbeltown had finally exploded. The dock was put out of action for the next 10 years.

As for Bill’s fate – his story only came to light a few years later. Making his way to his target, he turned a sharp corner and collided with a German soldier. Bill immediately fell backwards, most probably bayoneted. Corporal Maclagan, who was with him, shot the German and breathing heavily, Bill said:

“That you, Mac? Don’t stop for me. Go straight back and report to HQ. That’s an order.”

The Corporal reluctantly followed orders but on arriving at HQ, was told that any help for Bill was out of the question.

Bill’s remains were buried in Escoublac, some ten miles west of St. Nazaire. On his headstone are inscribed the words “Loved by all who knew him”.

Pritchard Court in Llandaff now bears his name and a plaque was recently unveiled to commemorate his part in the raid.