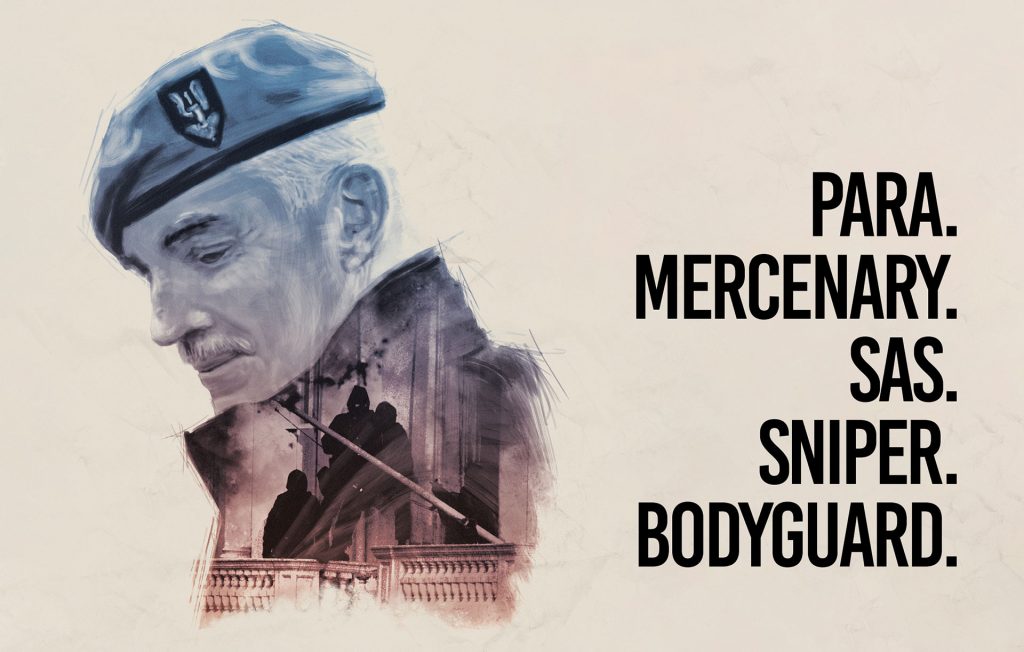

Robin Horsfall: Boy soldier to SAS

“I’ll have a bowl of porridge please.”

It’s early summer. In a small cafe, just outside of north Cardiff, Robin Horsfall is ordering breakfast.

Among the chatter of the cafe, most are unaware of the extraordinary life of the man with the moustache sat quietly in the corner.

“Until the age of seven, I had no father figure in my life,” says Robin. “There was a gap in my development because there was no one there to put me straight or tell me how to behave. As a result, I grew up lacking confidence and became vulnerable to bullies.”

Robin was born in Surrey and following a divorce from his birth father, Robin’s mother Hazel married what was to become Robin’s step-dad.

“He adopted me and gave me his name Horsfall. He had no experience of bringing up children and could get violent with the frustration of my behaviour.”

Robin’s broken family life impacted heavily on his education, and as a result, he developed a resentment to authority.

“Nobody asked me if I wanted to go to school. I tried hard there but I was always put down by the teachers. My voice was silenced.”

With his home life falling apart at the age of 15, Robin decided to join the Army as a boy soldier.

“I’ll always remember having to walk across a trainasium as part of our Para training in 1973. I was 16 years old. A trainasium is essentially two steel poles arranged almost symmetrically 60ft up in the air. My job was to walk across them but the thing is, there’s a six inch high scaffold clamp on each bar in the middle so you can’t just run across and get it over with quickly. You have to stay in control, adjust midway, and continue over.

“I got halfway and froze with fear. My trainer, a man by the name of Mick Lee, came up the other side and walked out to meet me. He actually held my hands and walked backwards across the bars until we got to the other side. Then he told me to do it again alone. Which I did. It was the first time someone had shown me what true leadership was.

“Joining the Army was my decision to let them have authority over me. I quickly became unhappy with failure. The only way for me to hold my head up was to excel – to be faster, fitter, and quicker than anyone else. I learned to stand up for myself.”

Despite bullying by his peers and colleagues in the forces, Robin became a full member of the Parachute Regiment in 1974 and served three tours of Northern Ireland as part of Operation Banner.

In January 1979, Robin passed selection for the SAS at his second attempt.

“SAS selection is nothing like it’s depicted on TV. There’s none of this shouting or criticism. Parts of the training took place here in the mountains of South Wales.”

On 30th April 1980, a group of six armed men stormed the Iranian embassy on Prince’s Gate in South Kensington, London. The gunmen took 26 people hostage, including embassy staff, several visitors, and a police officer who had been guarding the embassy.

Within 48 hours, the SAS had been dispatched and had set up camp in the adjacent building.

“We were there next door for most of the siege. No one knew we were there. We camped down in a surgeon’s office and I remember lying on the floor, fully kitted up, looking at the primitive-looking tools hanging up.”

By the sixth day, the terrorists’ patience had worn thin. They executed one of their hostages and dumped his dead body on the steps of the embassy. They told police negotiators that they were going to kill the rest of the hostages, one at a time, over the next few hours.

“The police finally handed over control to our guys and we all got into our assault positions,” says Robin.

To distract the gunmen, the SAS detonated a huge explosion to blow out the skylight on the embassy roof. As the world’s media watched, SAS troops then blew out one of the windows at the front of the building.

“I entered on the ground floor at the rear of the building. We could hear the commotion going on when the first blasts went off.”

The deadly raid lasted just 17 minutes. Five terrorists were killed and one was captured.

“We’d formed a human chain down the staircase to get the hostages out. We wanted to get them out as quickly as we could and we also wanted to get out of there ourselves.

“Then suddenly, someone shouted ‘He’s a terrorist!’ and when we looked, there was this guy stumbling down the stairs with a grenade in his hand.

“It was only as he came clear at the bottom of the stairs that myself and two other guys opened fire.

There was no warning shouted. He had a grenade. We shot him.”

The raid had brought the SAS into the public domain for the first time.

“At that point, we were the world’s most famous anonymous people.”

The following year, Robin married Heather and in 1982, during Operation Sandy Wanderer, Robin discovered a measles epidemic in the Bedouin population of Oman.

“We got some vaccines to them and saved a lot of lives, especially children.”

Later that year, Robin was heading to the Falkland Islands for what seemed like a suicide mission to destroy assets of the Argentinian Air Force. It was the first time since WW2 that the SAS were involved in large-scale conflict.

“I remember having to leave my pregnant wife and not knowing if I was coming back. That was hard.”

By 1984, and with a growing family, Robin decided to leave the Army.

“I bought myself out. I’d had enough. By 1986, I was bodyguard to Dodi Al-Fayed in London. I also qualified Black Belt in Karate.

“I then moved on to become a ‘contract soldier’ in Sri Lanka. I was only there a few months but I soon realised I’d made a mistake. There was a lot of genocide, torture and media control going on, so I left.”

In 1991, as the medical officer for a Gold mine in Guyana, Robin built a medical facility from leftover materials and as a Registered Emergency Medical Technician, he trained the staff there. In only four months, he’d completed his task, saving several lives along the way.

“Throughout the late 80s, I was bodyguard to leaders and politicians and by the early 1990s, I was teaching karate professionally in London. I set up my own karate school there before retiring in 2012.

“I broke my neck so that wasn’t good. My son now runs the school so we’ve kept it in the family.”

Yearning to assuage his creative streak, Robin completed an English Literature with Creative Writing degree at Surrey University in 2013.

“I was the only older man there so it took the students a long time to accept me.”

Robin has since written a number of books, and continues to write.

“It helped me through when I was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2018. The treatment was grim and although I never tried suicide, I did consider it an option – that’s how low I felt.” Robin now gives inspirational talks about his life, and recently raised £1,200 for charity at a talk held at Abercwmboi RFC.

These days, he resides in the South Wales mountains near where he started his SAS training in the late 1970s.

“It’s so quiet where we live. I’ve got time to reflect, to think, and to write. You’re never alone either – the community is so helpful. The mountains have been my playground so I feel at home here.”

Images: ©Crown Copyright and Robin Horsfall