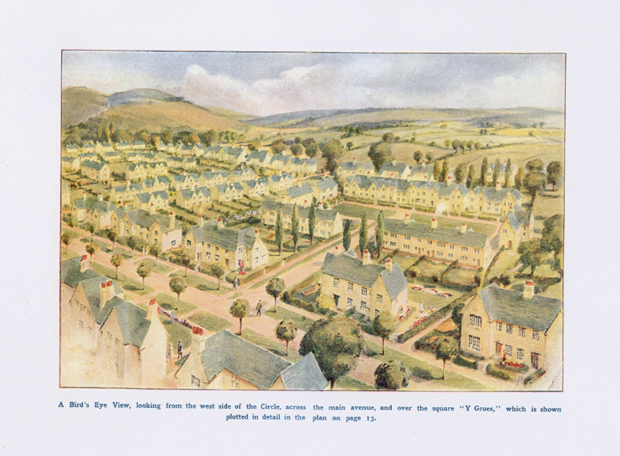

The Garden Village- a City in the Country

Rhiwbina’s famous Garden Village highlights many of the ideas developed by Raymond Unwin, one of the leading architects of the Garden City Movement.

The Garden City Movement was an approach to urban planning that was intended to be planned, self-contained, communities surrounded by greenbelts, containing carefully balanced areas of residences, industry and agriculture.

Development began in January 1912, when a small society was set up to ‘promote experimental suburbs’. Leading the way was Professor Stanley Jevons, Professor of Economics at University College, Cardiff who hailed from Llanishen. The society scouted Cardiff for a suitable site, before settling for what was known as the Pentwyn Estate in the north of the city. Although the aim of the society was to create a large suburb, the society erred on the side of caution and bought a 10-acre site at Rhiwbina Halt.

Construction work started on 34 houses (Nos. 1-22 Y Groes, 2-20 Lon Isa and Nos. 20-22 Lon-y-Dail) on a rainy day in 1913. A grand opening ceremony was held outside 6 and 7 Y Groes, where the Earl of Plymouth, Prof. Jevons and Raymond Unwin addressed the crowds.

The Great War of 1914 threw the entire project into uncertainty, and indeed in August 1914, the Society heard the crushing news that the Housing Reform Company, which was overseeing Garden Village projects over the UK, had gone into liquidation. It seemed as if the end was nigh.

In November 1914, Prof. Jevons set off to take up a post at Allahabad, India. He had done all he could to make the development a success, but in his farewell address to the Society, he spoke of ‘the great sacrifices he had made in pursuit of his objectives’. It is clear that Prof. Jevons lost a lot of his own money in the project.

The Society struggled on, and in 1915, their perseverance was rewarded when the Welsh Town Planning and Housing Trust very kindly took over all the Society’s debts totalling £22,000, and also provided capital that would allow the construction of more houses when the war was over.

Demand for housing in the 1920s was on the increase, and the Society gave precedence to married children of members of the Society.

In 1931, a great storm rolled in, causing the brook to burst its banks and flooding fourteen houses. Despite the added burden of the Great Depression, the Society set about doing all that they could to ease things for the villagers. Rents came down and they even took advantage of the empty properties to redecorate them and use them for marketing more houses.

In 1939, war broke out again. Housing developments were again put on hold, and the Wendy Hut, which had been used as a meeting place for the Society, was now used as an Air Raid Warden’s post. Evacuees moved into the village which was deemed comparatively safe, although other parts of Rhiwbina were hit by bombs and several houses were flattened. The Garden Village remained unscathed though.

After the war, the Society was forced to sell a number of properties as their finances had taken a hammering. But by 1968, their situation was so favourable, that a Special General Meeting was called, where tenants were told that they were to be offered the leasehold on their own homes on favourable terms. The crowd at first were stunned, but then broke into rapturous applause.

The Society wound up in 1976, when they announced that they could no longer look after the finances. All financial assets were given to local charities.

In February 1977, Cardiff City Council designated Rhiwbina Garden Village as a Conservation Area under the 1974 Town and Country Amenities Act. The Council wrote that:

“The area is of historic interest as a unique example of early 20th century village planning. The design embodies principles of pedestrian and vehicular separation not widely used until decades later. It was originally an estate of workers’ housing built in a semi-rural idiom, and was begun in 1913. Of special interest is the architectural style used throughout the Village, which utilises distinctive forms and a limited range of simple materials. Trees, hedges and greens were an integral part of the original design, and enhance the semi-rural character of the area.”

This meant that inhabitants within the area came under many regulations. Any demolition required planning consent; the Council could enforce works necessary to maintain the area’s character; and in addition, even the most important trees and hedges were covered by the Tree Preservation Order. Permission had to be obtained before any felling or pruning could be carried out. The Council even provided leaflets on how to maintain the character of the buildings.