Hunter: The Attack on Fort Harib

The attack on Fort Harib on 28th March 1964 was arguably the highest profile incident involving the Hawker Hunter during its eight years of operational service in the Middle East. The operation caused a political storm back in the UK and in the United Nations. Cardiff’s Peter Lewis was awarded the Air Force Cross for this and 118 comparable strike or surveillance operations. These are his words.

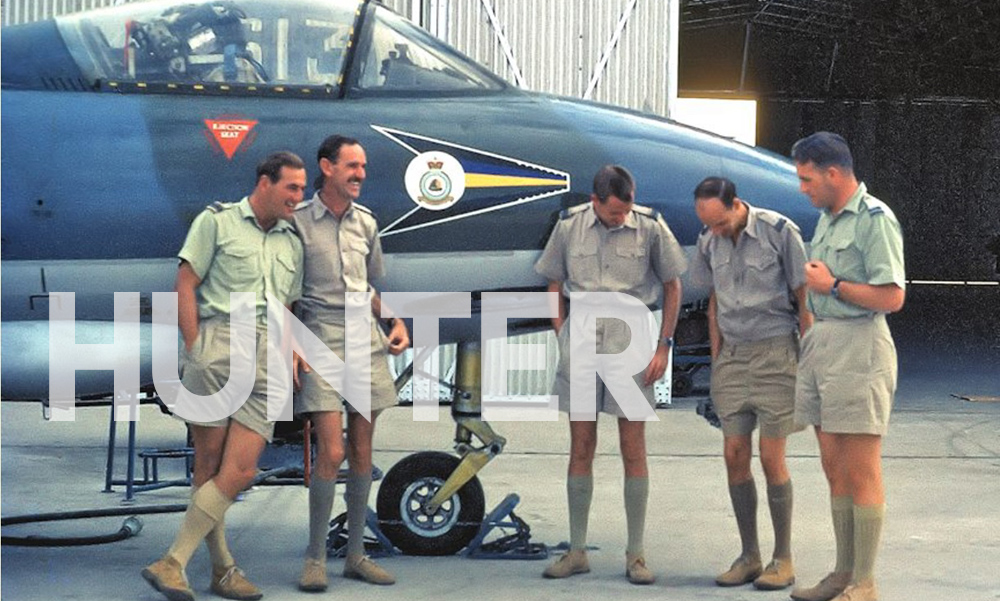

The pilots were Johnny Morris, a veteran from flying Mustangs in the South African Air Force in the Korean War; Jim Dymond, a PAI (Pilot Attack Instructor); Tony Rimmer, a past member of the Aden Protectorate Recce Flight, which had flown Meteor FR.9s in the late 50s; and Geoff Timms, a solid, quiet, ex-Halton apprentice. We were all over 6ft, all 30 or over, all married with children, and all were 2nd or 3rd tour pilots. All the ground crew were very experienced on the Hunters and were those that the squadrons didn’t want because they were difficult to manage!

The first task was to get the FR.10s back into shape. The FR.10 was undoubtedly the most beautiful of the Hunters. There was a lot of work for the ground crew; the Warrant Officer said that it would take at least a fortnight’s damned hard work to get those lovely jets back to the thoroughbred status they deserved. That was a blessing in disguise as we reckoned that we needed at least that time to get the rest of the Flight into shape! We were allocated a drop tank store as our accommodation and with a lot of help from the Station ‘Works and Bricks’, we did some DIY and set to building partitions to give us a ground crew room, a pilot’s crew room, an office for the engineering Warrant Officer, a little store, and somewhat against my wishes, an office for the Commanding Officer. ‘We don’t want him breathing down our necks all the time,” was one of the things I overheard. I got a nickname of ‘Prussian Pete’, and some months later, two little notices appeared on the door to that office; one read ‘Be reasonable, do it his way’, and the other read ‘Diplomacy Department. He says and does the nastiest things in the nicest way.’

I annexed one of the Wing T.7s (two seat Hunter) whenever possible, and flew with each pilot on a ‘QFI/IRE’ check ride. A bit laughable really – they were all damned good flyers, but it did demonstrate that we could follow as well as read the dreaded ‘Air Staff Instructions’. Johnny Morris meanwhile gave us all a very hard time on visual recce

Johnny taught us the importance of planning a good IP (Initial Point) which would give the best photographic run past the target whilst maintaining whatever element of surprise was going to ensure a clean getaway; the desert is a very quiet place, and the Hunter will have been heard long before it appeared!

The strike on Fort Harib began as an RAF classic. The wing had a stand down for two days, apart from one recce Hunter and four Day Fighter Ground Attack (DFGAs) who were on two hours standby. As a result, there was one hell of a party at someone’s house which went on a bit.

At around 4.00 am, there was a beating on the door, and there was Roy Bowie, the Wing Ops officer, saying ‘Get down to flights! We’re going to start some nastiness!’

The Wing Leader, John Jennings (JJ) had laid on a mass of toast and coffee, but as the briefing started, the adrenaline took over; I’m convinced that it is the best hangover cure there is.

The fort was to be leafleted fifteen minutes before eight Hunters led by JJ struck. Sid Bottom (8 Squadron) and I were to carry the leaflets tucked in our raised flaps and I was to photograph Sid’s leaflets going down on the fort. We were then to pull up to 30,000ft and keep an eye open for any opposition which might choose to join the party.

Once the strike was over, I was to photograph the fort again.

It was all going smoothly until while filming Sid’s leaflets, I saw at least one and probably three AA guns on the ground just to the south of the fort. There followed an agonizing fifteen minutes – break radio silence and warn the strike boys, or keep quiet? As the strike was going in from 20,000ft, the gunners would have to be pretty good to get a result and they probably weren’t that good, so I decided to shut up and sit tight.

I need not have worried. JJ led the eight Hunters down and his salvo was a ‘pickle barrel’ shot. I guess he must have hit a magazine or something as there was a huge yellow flash and a ‘mini mushroom’ of dirty brown and black smoke. I reckon that the other seven could only fire into the smoke and hope for the best but there were no more big explosions.

I told Sid to join the others and go home as it was going to take some time for the smoke to clear and allow a decent photograph. The smoke cleared after about half an hour and I made the second pass. The fort was an awful mess and there were several bodies lying about around where the guns were.

The thought occurred that JJ’s salvo had probably blown bits of the southern end of the fort all over the poor sods.

So far, so good. I reckoned that I hadn’t exposed too much film (a short length of

The MFPU did a smashing job and the film was on the light bench by the time I’d walked in and signed up. The photos were good and I marked the two I wanted printed up and went into the debriefing with them. I handed them to JJ and his face lit up with a smile which was a mixture of pride and relief. All he said was ‘Thank you 1417’. That was enough; and in the eyes of the DFGA boys, we’d arrived.

The SAS were very active in the Radfan and did a lot of surveillance of the enemy resupply routes. One morning there was a message that a camel train had been spotted the previous night, and was resting up near the Yemen border. I was sent up for a look-see, but despite being pretty sure I was in the right place, I saw nothing. Then a voice (on the R/T Operational frequency) said ‘They’re there’; that was all. So I looked more carefully. There was a sort of a track which followed the dried up bed of a stream, and which went through the odd pool of water which had not dried up.

I noticed that the colour of the track above these pools was different to that below them and remembered some of Johnny Morris’ training – the camels’ wet feet had probably washed the sand off the path below the pools. And then, suddenly, what had appeared to be just rough boulders, turned out to be couched camels; but no sight of any humans.

‘Time to help the Army’ I thought; I turned round and gave the camels no more than a two second burst of four guns, then turned again to photograph what I’d done. There was that brown/black smoke (as at Harib) all over where the camels had been, and no hope of any pictures.

On return to base, I asked Johnny Morris to go back up there and do some pictures but he came back without any; he said that there were so many vultures in the air and on the ground there was no way he was risking a bird strike just for my photo album!

There was a strange aftermath to this episode. Many years later, when I was out of the RAF and holidaying on the West Coast of Wales with the family on Dinas Head, I was having a lunchtime pint in a pub called The Sailor’s Safety when a voice said:

“It’s Peter Lewis isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I said, “but do I know you?”

“Better than you know,” replied the man. “Do you remember some camels up in the Radfan?”

“Yes.”

“And someone telling you they’re there?”

“Yes.”

“Well that was me.” The man speaking was the local postman.